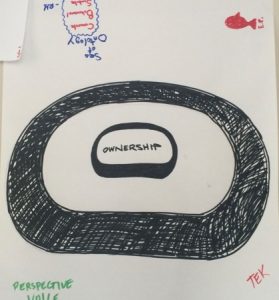

(1) At the heart of multicultural learning is the realization/understanding that everyone comes to a learning environment with a different background that has not only shaped all of their past experiences, but that continues to inform their understanding of the world. Background is everything – it creates your context and in a very real way, this subjective experience actually creates its own world.

Most humans default mode is powered under the assumption that their interpretation of events is just the way it is and most people probably don’t even think about their reality as actually BEING a subjective viewpoint. Teachers however cannot do this and be effective with their minority students. Though it is the dominant culture’s privilege of power to not have to worry about how minority cultures perceive the same events, teachers cannot avail themselves of this privilege.

This blindness and assumption is exactly what happens within the American cultural tapestry, all the time. All of our threads, our subcultures, are interwoven, but many, maybe most of us can’t feel very far beyond our own individual cultural strand. We only become aware of other cultural strands in our grand tapestry when our lives wind around them. Most times, we just run along the texture of our own thread.

It’s at these moments of interfacing, (which as teachers we will have every day) we must try to see the world as it is through our students eyes. My goal as a teacher is to try and introduce critical thinking and effective communication skills by reaching these students through my own embracing/understanding their own cultural backgrounds. I will try to find their “nodes” of experience and use those to transmit these general skills and abilities. To paraphrase the rapper 50 Cent, I’m going to get multicultural or die trying.

(2) Tolerance, Synthesis and Transformation: this is more than one term, but it is one process. I think that this is a good intellectual map to use to check up on oneself when interacting with student cultures that are outside of my own; Concrete, Behavioral, Symbolic: this is kind of the Architecture of Cultural Consciousness and is a very good schematic to think about how deep one is going when interacting with another culture. Ex. Are you “just” having students draw their own totem poles, or are you talking about how those values embedded in the totem pole speak to Tlingit culture? The symbolic level of understanding will be beyond most cultural outsiders (like myself) but is still a good descriptor to help understand the different levels of cultural depth; Background: I talked about this above, but background is always key. If someones background changes their perception about a given situation drastically enough, all of your assumptions about how to teach someone will be in error.

(3) The techniques that I will use to teach effectively beyond my culture will come down to strategies like I outline in my lesson plan for the ibook. My passions in life have been Alaska and foreign cultures, particularly in Asia. Wherever I teach in Alaska I will try and find works of local culture (not always Native Alaskan necessarily, but quite often I’m sure) and compare/contrast those works with complementary cultures from abroad. I hope that by showing my students how local culture and other further flung, but still somewhat similar cultures, are related/not related, that they will then be able to see the metes and bounds of their own local cultures much more clearly. I believe that we truly only learn about the depths of our own cultures by holding them up to Another Culture/Another World, to paraphrase the title of the book that started this class.

I will be in Sitka in the coming year. Hopefully I will be able to access Tlingit myths and history (including hopefully have an Elder come in) and compare those to other stories and history in the Pacific Rim. After all, Sitka fronts the Pacific and faces Asia. I think it would be fascinating for the students to compare the history of Sitka (especially from European contact on) with Commander Perry’s opening of Japan to trade withe U.S. with “gunboat diplomacy.” Likewise Britain’s exploitation of China for the tea and opium trade, the incredibly bloody seizing of the Phillipines by the U.S. navy, the betrayal of the Korean emperor/people by the progressive President’s Roosevelt and Taft by giving the green light for the Japanese seizure of Manchuria. It goes on and on really. I want to show students that their local stories, their local history and even their art is not isolated, but that’s its part of a greater Pacific international human experience.