When I think of culturally responsive teaching, I think of the words grounded, rooted, and integrated. Grounded in culture, rooted in culture, and fully integrated culturally. A culturally responsive lesson does not just showcase or highlight an aspect of the regional culture in which students are studying – it digs its roots deep into those ways of knowing. It is reflective, interactive, and responsive (as it says in the name!), not a mere snapshot or a “heroes and holidays” approach.

All of the lessons we observed and participated in this past week allowed us (and the culture camp students) to learn about and actively engage culture. Something I liked about each lesson was that all of them required students to think critically and make meaning. Actively engaging culture, thinking critically about culture, and making meaning from cultural knowledge are three hugely important features of culturally responsive teaching, as was evidenced in each lesson presented in class last week.

Observing the culture camp was an enlightening experience. From observing the students, you could tell that they were engaged and excited about what they were learning; I think that this was due to the hands-on nature of the camp – the fact that they could actively participate in the exploration and acquisition of knowledge. They could make the knowledge their own by doing, not just by listening. I heard several students say that attending camp was a transformative experience for them. Having the chance to be an active learner can be truly empowering. The evidence is in the students’ reactions.

I was so impressed by how immersive, interactive, and interweaved the learning process was at the Goldbelt Heritage Institute culture camp. Whether the students were fluent in Tlingit or only knew a few words, they could all participate on their own level and learn more about their language. When Lyle spoke with his students, he said everything in Tlingit and then in English – an immersive and bilingual approach to learning. This meant that the use and practice of language was prominent in every lesson the students learned, whether that lesson was about dance, native plants, or learning how to process a seal. The students learned about the native plants and animals in the field, in the natural landscape. Learning about the land on the land is much more powerful than learning about it in a textbook or a laboratory. They learned valuable life skills rooted in culture and the environment: how to forage, eat, live, survive, and thrive off the land. They learned how to process, prepare, and smoke seal and salmon. They learned how to de-quill a porcupine and prepare it for cooking. They learned about edible plants like the rice that grows at the roots of the chocolate lily. They learned about dance and storytelling. One of the lessons that really intrigued me was Jasper’s lesson about porcupine bile. Jasper taught the students about the medicinal uses of porcupine bile, and he created a science experiment to test its antibacterial qualities. He had the students place some porcupine bile (collected from the porcupine earlier prepared for food) into petri dishes that contained bacteria samples and then test to see if the introduction of the bile caused a decrease in the number of bacteria in the petri dishes. This was a great example of a culturally responsive lesson that allowed the students to engage with science, nature, and native medicinal techniques.

Back in the classroom, we had the chance to observe and participate in three culturally responsive math and science lessons. These three lessons embraced, engaged, and integrated aspects such as history, the natural environment, and Native Ways of Knowing. In Tina’s math trail, we got to experience place-based learning by engaging our natural environment. The math trail integrated some of the history of the area around UAS by including questions incorporating the raven and eagle totem poles, as well as pieces of native art located on campus. The math trail pushed us to interact with our environment by observing, measuring, and estimating the size of objects located in the place in which we were learning.

In Paula’s science lesson, we learned about a series of data collection projects her elementary science students completed. The students participated in a jellyfish investigation, a mussel investigation, a berry picking investigation, and a historical places investigation. These activities are examples of place-based investigation. In each investigation, the students were given the freedom to design their collection methods and style of analysis. In this manner, they were allowed to research and gather information according to their own learning styles and embrace their creativity rather than be limited to one way of thinking. This lesson demonstrates culturally responsive methods because it allows the students to draw on their prior cultural knowledge and embrace their personal creativity. By not enforcing a specific method of collecting data, Paula allowed the students to explore according to their own learning styles and inspiration. This is a great way to make science accessible to more students! By having the students present their findings from their investigations to the community, Paula made this a community-engaged lesson, connecting the students with the other residents of their locale. By conducting the investigations out in nature, the students were given the chance to interact directly with their environment. I wish that I had had more science lessons like this as a child! Learning would have been much more engaging.

In Angie’s lesson, we engaged our natural environment, local history, and Native Ways of Knowing. We learned about the medicinal properties of sphagnum moss, a type of moss that grows locally in the boggy areas around Juneau. This lesson was particularly engaging because it integrated history, medical techniques, and native plants. We learned about the absorbency and antibacterial qualities of the moss through reading and through experiencing it ourselves. Our task was to test the relative absorbency of sphagnum moss vs. modern diapers using whatever data collection methods inspired us. This opportunity for creativity, exploration, and innovation in the science classroom made the experiment riveting and immediately relevant. We discovered firsthand that the sphagnum moss was significantly more absorbent! This experiment was an excellent example of place-based learning, and it connected us with the natural landscape in a meaningful way because we got to be part of a hands-on experience.

Each of these lessons involved observation, critical thinking, analysis, creativity, and freedom to explore – all important aspects that both engage the student and forge a deeper connection with place.

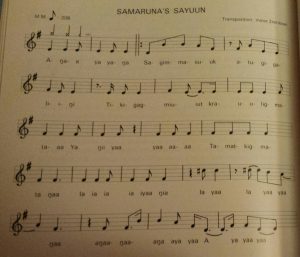

As a music teacher, I plan on incorporating culturally responsive teaching techniques into the classroom by integrating traditional music selections and place-based learning into the curriculum. I can offer a broader, more diverse, and more inclusive music education by presenting diverse styles and histories of music rather than solely focusing on western classical music (as has been the status quo in American music education for ages). In tandem with teaching classical music, I can teach songs, melodies, and pieces from Tlingit, Yup’ik, Inupiaq, Athabascan, and Aleutian culture, as well as other traditional musics from around the world. I could have my students conduct world musical investigations by researching the music of a specific place and then bringing in recordings and sources to share their new knowledge with the class. This would be a great way to get the students involved in self-guided musical explorations and expose them to the diversity of music in the world. Another way I could have students engage with music in an interactive way would be to have them explore the sounds of their surroundings. I would plan a field trip day where the students could go out into the environment and explore and record the sounds of their local surroundings. Then, they could come back to the classroom with those recorded sounds and use them to weave their own piece of music.

___________________________________________

Updated Thoughts on CRT:

After this week’s presentations on more examples of culturally responsive teaching, I feel like I better understand more approaches to creating culturally responsive lessons. With the diversity of lessons and ideas presented, we were shown that there are endless ways to create culturally responsive lessons and encourage students to think critically about culture, history, and social dynamics. I feel like I now have more tools in my toolbox for implementing a wide array of culturally responsive lessons in the classroom. I learned that culturally responsive teaching can be both a way to preserve and honor culture and a way to challenge the status quo.

Michelle’s lesson allowed students to uncover information and make inferences about Alaskan World War II history on the islands of Attu and Kiska. Her approach let students take ownership over their learning process by letting them discover the knowledge through exploration. This approach allowed the students to form their own impressions and uncover answers about the war’s impact in the Aleutian Islands. I like that Michelle’s lesson gave students the opportunity to learn about an aspect of American history that is rarely covered in the history books. Her lesson helps to expose students to the injustices that occurred in the Aleutian Islands during the war.

Alberta’s presentation provided great perspective on inviting and integrating Elders into the classroom. She gave an in-depth look at all of the aspects a teacher needs to consider when reaching out to an Elder. This was very enlightening for me, as I am a newcomer to Alaska. After listening to Alberta’s talk, I feel that I have more insight on how to ask an Elder if they would be willing to share their wisdom in the classroom, and this process does not feel as daunting anymore. I am glad that Alberta was able to share some of these procedures and protocols with us.

Scott presented an interesting take on place-based learning, one which I would be interested in implementing in the classroom. In Scott’s lesson, he had his students explore their locale by documenting the people and places around them and compiling that information creatively to make a book. He took the idea of “What do you know about the history of your place?” and let students both explore and draw upon their prior knowledge in order to uncover and synthesize information about place. I was very inspired by Scott’s innovative project-based learning approach, and I could definitely see myself employing a similar idea in the music classroom. I would be interested in having my students do a place-based exploration where they document sounds, people, and events to capture a musical landscape and history of a place.

In Kathy’s lesson on multicultural storybooks, we learned how to apply storybooks in the secondary classroom as a way of broaching larger concepts and social justice issues. We experienced multicultural literature as a vehicle for addressing and challenging power structures. I was moved to realize that story can be a truly powerful tool to address social inequalities and can help students to gain awareness and take action on those issues.

Of the five culturally responsive experiences we explored, I think that Ernestine’s words were the most impactful for me. She is such an advocate for students and for radical change in our education system. Her words hold such incredible power and implore us to be agents of positive change as educators: “You’re not going to save them. You’re going to believe in them. And they’re going to save themselves.” “If you’re not combatting colonialism, you’re continuing to ingrain it.”