Selina Everson fights for Tlingit language and culture preservation. She grew up speaking Tlingit. It was her first language. At school, she was told to speak only English. Ms. Everson broke that rule and courageously spoke Tlingit anyway. Ms. Everson remains a champion for her culture as a Tlingit language teacher. She’s known as “Grandma Selina” by hundreds of children at the school where she teaches. http://www.sealaska.com/why-we-do-it/our-people/our-champions/selina-everson

In my reflection, I want to speak on Selina Everson’s words, specifically in regards to Selina’s experiences with cultural preservation and destruction and how her words help me examine my own past. It was touching for me to see how Selina felt healed and empowered in connecting with children through her native tongue, Tlingit.

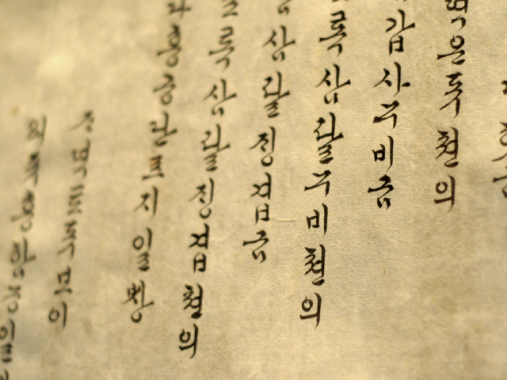

When Selina said “can you imagine what it must feel like to be told not to speak your own language?,” I silently nodded in response. I grew up in Korea, thus speaking Korean, and perceived the world through the Korean language. Like a fish unaware of the existence of the water it lives in, my life posed no cultural conflict, considering the fact that I lived in a country that is 98% ethnically Korean. When I moved to the United States at the age of nine, however, I faced waves of culture shock and trauma, similar to that of Selina’s childhood. My mother, in her well-intended hopes of integrating her children into the “American” systems/communities as quickly as possible, encouraged my sister and myself to assimilate in our customs and in our language. In the schools, my classmates made fun of my attempts at pronouncing such simple words or names like ‘Benjamin’ or ‘Tadpole’. Once a week a Spanish teacher came into our class to teach us words in Spanish, to my utter confusion. When my parents made the decision for my sister and me to move to the U.S., what did that mean? Were they implying that the culture of America was better than that of Korea? I was left with more questions than answers, and in my struggles to find an answer, was instead left with shame, resentment, jealousy, and fear. I hated the fact that my love for tofu or my preference for rice over bread would marginalize me, and I hated even more the fact that I was Korean. I wish I were White was not an uncommon thought throughout my childhood. I wish I were as brave and firm as Selina had been, a lone soul facing a crowd of judgment.

Selina also spoke of a moment of empowerment and self-gratification (I wonder if anybody else felt the quenching peace in her deep breath) when she had a positive response to her speaking Tlingit to a group of children. A significant turning point for me–which was also a point of ultimate healing for me–was in the summer before my senior year in college, when I worked as a residential counselor for a pre-college program for high schoolers from around the globe. Students from Dubai, Kuala Lumpur, Spain, etc… were all present on campus, learning together and living together. After finding out that I was bilingual, a Korean immigrant student began speaking to me in Korean, to which I responded to in English. I let the student know that it might be unfair for the other students to not be able to understand what we were saying. (Even as I am writing this I am saying to myself, what was I thinking?) It was at this moment when a student, who was observing our interaction (the Korean student speaking to me solely in Korean, and me, responding solely in English) said to me, “Did you know that you just translated what the student was saying in Korean and formulated a response in English without even thinking?” I was shocked at this comment. My ability to perceive the world in two languages and in two cultures proved to be an amazing gift. I genuinely felt proud of my heritage, and in that moment, the weight of my adverse childhood experiences became forged into one of the greatest tools that I own.

Like Selina, a sense of hope was planted in me, and since then, I look for ways to share my Korean culture, often by introducing Korean objects and foods in the concrete-level, but also by sharing the ways in which the Korean language has shaped my way of thought. I know that this passion of mine will be crucial, in my hopes of connecting with students in ways that I can celebrate both my background, as well as the background of others.

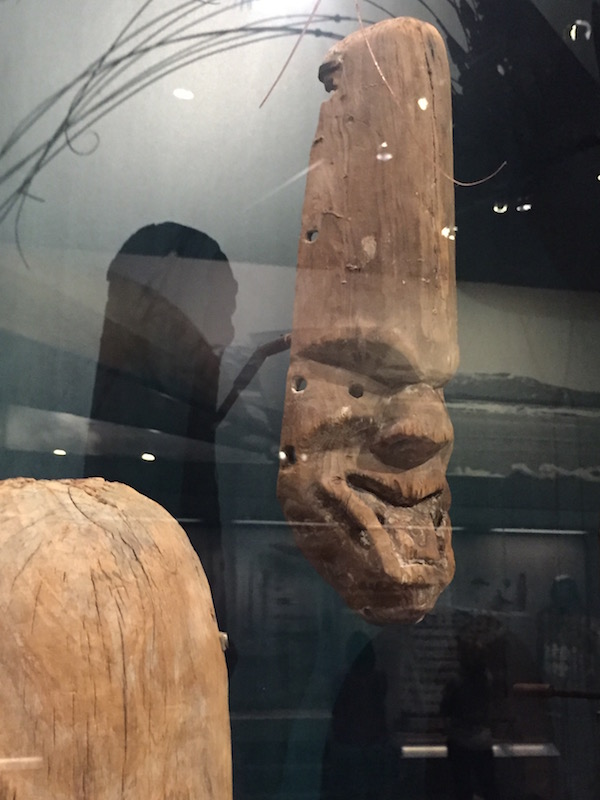

The Giinaruaq Masks displayed in the Alaska State Library Archive Museum (SLAM) originate from the Sugpiaq/Alutiiq communities spanning the Southcentral and Western Maritime territories of Alaska, stretching from across the Alaska Peninsula, the Kodiak Archipelago, the outer Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound.

The Giinaruaq Masks displayed in the Alaska State Library Archive Museum (SLAM) originate from the Sugpiaq/Alutiiq communities spanning the Southcentral and Western Maritime territories of Alaska, stretching from across the Alaska Peninsula, the Kodiak Archipelago, the outer Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound.