Here we are today in Juneau, Alaska, looking at places and peoples that adapt, change, grow and are part of a very interconnected world. I thoroughly enjoyed spending the morning at the SLAM! There were so many items that caught my eye. I actually had a hard time focusing on one object of interest as the whole exhibit was great and i have so much to learn and go back to explore. So many different places, cultures and times to research. And through looking at various classmates posts, I realize I didn’t even see the entire museum…

Glass Trade Beads- from China or Italy courtesy of Alaska State Museum – Juneau

The item I chose to focus on caught my eye because, well, I love beads. And these beads were presented as ‘either from Italy or China that had been traded in Alaska for centuries.’ WHAT?!

The exact date or artist of these Alaskan pieces, or whereabouts of where the pieces were found were not given, or was the political climate around these trading of goods. They are not from thousands of years ago, but only centuries ago. But the entire history of Alaska is rich. What I love about these beads are the stories they must tell. They came from far away lands and must have been popular and worth a lot (in their time) where they came from if they were to be traded in Alaska for rich furs and oils. They made their way to Alaska and these beads impacted the artistic and cultural landscape here. Fashion continued to change- as it does now.

These beads were brought over the Silk Road and the tea trade routes of Asia.. Many people of Tibet and western China love the use of beads as well and I am fascinated as to how, before airplanes and telephones, this trade, as well as a common trend, so easily happened from so far away! Here is a picture of a woman from Eastern China this past summer adorning her beads:

The beaded jewelry in the museum caught my eye and has perked my interest in the continued study of the areas of the Pacific Rim.

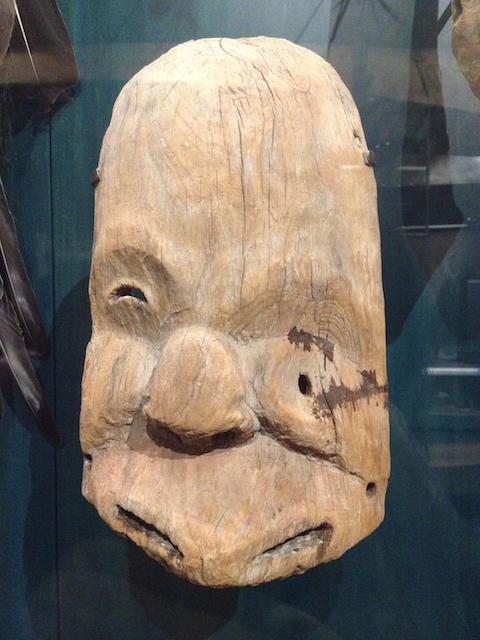

The Giinaruaq Masks displayed in the Alaska State Library Archive Museum (SLAM) originate from the Sugpiaq/Alutiiq communities spanning the Southcentral and Western Maritime territories of Alaska, stretching from across the Alaska Peninsula, the Kodiak Archipelago, the outer Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound.

The Giinaruaq Masks displayed in the Alaska State Library Archive Museum (SLAM) originate from the Sugpiaq/Alutiiq communities spanning the Southcentral and Western Maritime territories of Alaska, stretching from across the Alaska Peninsula, the Kodiak Archipelago, the outer Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound.

courtesy of

courtesy of